Inciting Democracy: A Practical Proposal for Creating a Good Society

Chapter 4: Elements of an Effective Strategy for Democratic Transformation

Download this chapter in pdf format.

In This Chapter:

How can we surmount the five obstacles to fundamental progressive change described in the last chapter? What is an effective strategy for creating a truly good society?

Since we have never created a truly good society before, the best route is unknown.[1] Still, we can learn from the past. This chapter examines the historical efficacy of several approaches and identifies a few crucial characteristics of a strategy to bring about fundamental change. It also describes six specific components that an effective strategy must incorporate.

Some Strategies of the Past

In the past few hundred years, activists have employed many strategies in an effort to bring about fundamental change. All of these strategies have been effective at various times and to various degrees, but each has drawbacks.[2] As I see it, an effective strategy for bringing about fundamental transformation would include the best of each of them while avoiding their limitations.

Violent Revolution

As it is usually understood, a revolution is a violent struggle for control of a society — a struggle that may involve mass uprisings, civil war between competing armies, drawn-out guerrilla warfare, or a quick coup d’état. A revolution usually involves a series of complex processes progressing through many stages. These include the breakdown of the existing order, competition among all the new claimants for central authority, and the building of new institutions.[3]

If we don’t change direction, then we’re likely to end up where we’re headed.

Revolutions are riveting spectacles that attract wide attention, interrupt people’s daily routines, and jar their sensibilities. If successful, revolutions expeditiously replace old powerholders with new ones. Even if not completely successful, revolutions forcefully challenge the existing order and raise the profound question “What is the proper governance of society?” By risking their lives for a cause, revolutionaries provide an inspiring model of action that compels others to examine themselves. All of these aspects of revolution are valuable characteristics of an effective change strategy.

However, because of their violent nature, revolutions are usually bloody, chaotic, and terrifying. Typically, large numbers of people experience horrible personal tragedies that deeply affect them for life. The victors — often those who fought most savagely — are typically shell-shocked, arrogant, and filled with hatred and bloodlust. The revolutionary process has taught them how to kill and destroy but not how to build anything positive. Over the course of the struggle, they may have come to value secrecy, trickery, and duplicity if this knavery led to victory. After the revolution, they seldom want to share their hard-won power with others. Instead, they typically brandish their weapons at anyone who challenges their absolute control.

Rather than democratizing power, revolutions typically just shift authority from an old oppressive elite to a new oppressive elite. When old institutions are destroyed, new institutions must be cobbled together hastily and so are often built on the same reactionary assumptions as the old.

For example, following the French Revolution of 1789, members of the old elite were executed in a “Reign of Terror.” The resulting power vacuum led to a major struggle among the revolutionary leaders, which was ultimately resolved when Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself emperor and launched a military conquest across Europe. This new dictatorship was no more democratic or enlightened than the old monarchy.

The surface of American society is covered with a layer of democratic paint, but from time to time one can see the old aristocratic colors breaking through.

The American Revolution of 1776 was more successful in democratizing political relationships — giving common people some voice in the government and offering a greater chance of fair treatment — but it did not end rule by plutocrats. Instead, it transferred control from the old, British elite to a new, American elite principally composed of rich men of English background. Women, slaves, the poor, and Native Americans were still excluded from the halls of power. Similarly, the Russian revolution of 1917 deposed the Czar, but it did not democratize the political system. Within ten years, control was concentrated in the bloody hands of Joseph Stalin.

Historical Materialism

In the mid-1800s, German intellectual Karl Marx wrote several books that radically influenced progressive change strategies.[4] Marx believed in historical destiny, specifically that capitalism had naturally displaced feudalism and eventually socialism would displace capitalism. He believed that when conditions deteriorated enough, oppressed industrial workers would see the contradictions in capitalist control. He assumed they would rise up, overthrow capitalism, and create a powerful workers’ state that would then, after a time of consolidation, wither away and give rise to a good society.

Though Marx’s critiques of capitalist society have been quite useful, his ideas about social change are less valuable. A century and a half after he first promoted his ideas, the workers’ revolution he foresaw has still not come about.[5]

A Vanguard Party

In the early part of the twentieth century, Vladimir Lenin developed a strategy to bolster and accelerate Marx’s historical destiny and ensure it took place sooner rather than later — even under the harsh conditions of czarist Russia. Lenin urged radical intellectuals and workers to build a vanguard party of disciplined cadre who could then educate and “revolutionize” industrial workers to overthrow the owning class. This strategy largely worked and helped to ensure the success of the Russian revolution.

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

However, as demonstrated so poignantly in the Soviet Union, when a vanguard party successfully wins a revolution, it often becomes as oppressive as the regime it overthrew: democracy is cast aside and replaced by overbearing bureaucracy and Stalinist purges. The strict obedience demanded by most vanguard parties is inherently dangerous and easily abused.

Countercultural Transformation

In the 1830s and 1840s, utopian intellectuals in the United States started a number of small, socialist communes that practiced and promoted various “countercultural” ideas. Since these communes were started by diverse groups of Christian and secular communalists, spiritualists, and sensualists, their ideals ranged widely. For instance, some — like the Shakers — promoted strict celibacy, whereas others promoted group marriage, and still others advocated free love.

Though diverse, these communities each sought to infuse their ideas and morality into society. This change strategy was somewhat successful: their ideas influenced the campaigns of the time for educational reform, women’s rights, and the abolition of slavery. They also inspired several popular utopian visions such as Henry George’s Progress and Poverty, Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward, and William Dean Howell’s A Traveler from Altruria.

However, these visionaries were naïve about social, political, and economic realities. They overestimated the skill of their members and underrated both the depth of cultural socialization and the depth and severity of their members’ emotional conditioning. They could not successfully insulate themselves from the pressures of capitalism or the influences of the dominant culture. By shunning political parties, labor organizations, churches, and the professions, they disengaged themselves from political and social life and excluded themselves from the councils of power. Eventually, their communes disintegrated from internal or external pressures or faded into bland, conventional institutions.

The counterculture movements of the 1920s and 1960s met a similar fate. Though influential, most of the communes spawned by these movements eventually unraveled. Counterculture ideas were largely drowned or distorted beyond recognition by the dominant culture.

Alternative Institutions

The Populist Movement of the late 1800s sought to establish people-controlled banks and cooperative ventures to avoid or undermine the economic elite who controlled conventional banks and railroads.[6] They were able to create some alternative institutions — a few of which still survive such as the State Bank of North Dakota.

However, without changing the fundamental nature of society, these institutions were left vulnerable to constant attack. Over time, most fell to the wayside or were destroyed by economic competition. Most of the many cooperative retail stores founded in the 1930s and 1960s, which were owned by consumers or employees, met the same fate. For example, in the San Francisco Bay Area, the Berkeley Co-op Markets, with ten stores in the East Bay, collapsed in the 1980s.[7]

Mass Advertising

Beginning in the 1830s, steam-powered printing presses and an expanding railroad network made it possible to disseminate information quickly throughout the country. Nationally distributed newspapers and magazines provided a medium for national advertising, which could sell brand-name products at a premium price. Soon the same advertising techniques developed for selling Ivory soap nationwide were employed to convey political and cultural ideas.

In an age of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.

In the 1930s, President Roosevelt used broadcast radio to sell his New Deal programs to the public. At the same time in California, conservatives used propaganda films to help defeat Upton Sinclair’s progressive End Poverty in California (EPIC) campaign. Using similar means, Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, created a variety of appealing messages to ignite support for Nazi nationalism.

Political campaigns today rely heavily on advertising to influence public opinion. Using polling and focus groups to determine what people want to hear and what messages they will accept, politicians then formulate clever advertisements and broadcast them widely and relentlessly.

Presumably, mass advertising could also be used to promote progressive change. However, progressive activists seldom have the financial resources to mount a large advertising campaign. Even if the money were available, most media outlets — controlled as they are by the power elite — will not broadcast messages advocating fundamental progressive change. Furthermore, by its very nature, advertising is much better suited to disseminating inflammatory propaganda and mindless rhetoric than at presenting thoughtful commentary on the value of progressive change.

Progressive Change, Inc.

If a large corporation, with vast resources, decided to create a good society, it might go about it like this:

First, the company would hire thousands of employees to do all the necessary work. Researchers would design and test alternative institutions, and engineers would develop plans to implement them. Thousands of well-paid employees would build and deploy them.

The company would hire an advertising agency to craft clever messages extolling the virtues of these alternatives and the defects of existing options — then massively advertise on television, in magazines, and in newspapers. To attract attention to the campaign, it might mail calendars, refrigerator magnets, and plastic ice scrapers, imprinted with change messages, to every household.

The company would contract with consulting firms to prepare reports that proved the superiority of progressive alternatives, and then mail these reports to opinion leaders in every community. It would hire prominent citizens to personally lobby in Washington and pay thousands of citizens to call or personally lobby their government representatives. It would finance progressive candidates to challenge officeholders who resisted change. It would also hire scores of slick lawyers to sue for change.

It would hire an army of attractive young salespeople who would present alternatives at gala events in fancy hotel ballrooms or even demonstrate them door-to-door. It would encourage people to “test drive” the alternatives.

In reality, there is no large corporation with the goal of creating a good society, and progressive activists do not have the resources to mount such an expensive change campaign. Even if it were possible, this description shows that this process might very well fail anyway. A top-down approach might disempower and corrupt people as much as it promoted progressive change, creating a mere caricature of a good society. At the end, we might have only an imprinted refrigerator magnet to hint at what might have been.

Technological Advances

Throughout history — especially in the last few centuries — many people have hoped that advances in technology would naturally generate a good society. They have believed that advances in medicine would reduce illness and mortality and that development of new devices (like automobiles, airplanes, and computers) would make life easier and more enjoyable. They assumed that automation would enable people to work less. With more leisure time, people could better support their friends and neighbors, and they would educate and improve themselves.

Technology has fulfilled some of this promise. We have better food and medicine than our ancestors, and we live longer. We travel more and farther. We can easily communicate around the world. We can read books, listen to beautiful music, watch movies any time we want, and access a wealth of information through the Internet. We have many more dazzling toys — delights that the richest nobles of a few hundred years ago would envy.

Still, as implemented in this society, technology has also caused great problems. The environment has been ravaged. Noise has increased. Our lives have sped up, leaving us frantic and exhausted. Many people work as hard as ever while others have no job and live in poverty. Some people live in palaces, but others have been driven into the streets. Inane advertisements intrude into every facet of our lives. Technology amplifies the power of crazy people who now have the means to kill hundreds of innocent victims with weapons of incredible firepower. People halfway around the world can now threaten us with nuclear-tipped missiles. Technology also makes it much easier for the police — or other agents — to spy on us in a variety of ways.

Clearly, by itself technology does not create a good society. Rather, technology appears to accelerate and intensify both good and bad social trends.

Conventional Electoral Politics

If voting could change anything, it would be illegal.

Since the founding of the United States, activists have lobbied and pressured officeholders and attempted to elect advocates of progressive change to office. They have been somewhat successful in both endeavors, but they have not been able to bring about fundamental change. The founders of this country structured the political system to impede rapid or radical change. Winner-take-all elections favor bland centrists and opportunists. Judges with lifetime appointments can block significant change for decades. Moreover, as described earlier, the control exercised by elite interests over elections and their domination of lobbying ensures the dilution or derailing of most progressive initiatives.

Conventional politics also has limited influence on the economic, social, or cultural aspects of society. As currently structured, the economic system is mostly immune to progressive political intervention. Instead, large corporations and trade groups largely shape it. Corporate advertising influences our culture more than do government, schools, or churches. The distribution of real estate — that is, affluent white people living in one neighborhood separated from poor people of color living in another — more effectively molds social interaction than any government policy.

Hence, though progressives have used government to make some changes, they have not been able to use it to bring about fundamental progressive transformation. Without major changes in the election and governing systems, progressives will probably fare no better in the future.

Mass Social Movements

Periodically, mass social movements have arisen and challenged the established order. Some have been quite large and powerful. For example, the civil rights movement of the 1960s ended discrimination in housing, transportation, and education and eliminated most barriers to voting in the South.

Typically, these movements have used a variety of tactics — such as leafleting, public speaking, strikes, boycotts, and sabotage — to pressure and undermine the power of authorities. Because social change movements rely on large numbers of people for their strength, the divergent perspectives of participants about goals and tactics can tear the movement apart. They are also vulnerable to the ignorance and conditioning of participants. In addition, they are vulnerable to infiltration and disruption by authorities. So far, no social movement has been large enough to bring about fundamental transformation of society.*

* The rest of this book describes a project for overcoming these limitations.

Incremental Change

In the last century, progressive change theorists in the United States have generally advocated one or a combination of these strategies. However, the limitations and historical failures of each loom large. While theoreticians have argued about the hypothetically best strategy for fundamental change, most contemporary activists have ignored them. Instead, activists have pragmatically focused on a particular injustice and used whatever change tactics seemed to work best in the short run, hoping that eventually it would lead to fundamental change.

No matter how far you’ve gone down the wrong road, turn back.

This strategy has typically included limited advertising (direct mail, leaflets), grassroots canvassing, lobbying, and supporting liberal politicians — spiced up with occasional civil disobedience, strikes, and boycotts. This strategy has brought about some positive changes, but clearly, it has not yet created a good society. With only limited resources, it probably never will.

Crucial Characteristics of

Fundamental Change Efforts

The deficiencies of these historical strategies and the obstacles discussed in the previous chapter offer some important lessons for developing an effective strategy for fundamental progressive transformation. The effort to bring about change must be:

Powerful and Inspiring

The forces maintaining the current society are extremely powerful. As described previously, members of the power elite control vast resources that they actively deploy to thwart progressive change efforts. Moreover, all of us carry counter-progressive tendencies induced by dysfunctional aspects of the dominant culture and by emotional conditioning. These tendencies are difficult to identify, challenge, or change.

The meek shall inherit what’s left of the earth.

To counter these powerful forces requires equally powerful counter-efforts. A large number of people must work assiduously and skillfully for progressive change, probably for many decades. Eventually, the vast majority of people in our society must be involved in progressive change efforts. They must vigorously challenge the power elite, the dominant culture, and their own internalized emotional demons. Strategies that rely only on new technology, individual goodwill, or “working within the system” are not powerful or direct enough to dislodge the elite or dissolve calcified social norms.

Focused on Broad, Fundamental, and Enduring Change

Society is an agglomeration of individual people. Individual people staff institutions, and individuals transmit cultural norms. However, individuals are not entirely autonomous agents: cultural norms shape individuals and large institutions pressure and constrain them.

An effective strategy must therefore change all three of these entities: institutions, individuals, and our culture. It must fundamentally transform each of them so they do not revert to the old ways after a short time. Change must be deep and broad enough and it must coincide with other changes so that a change in one area is not undone by still unchanged individuals, institutions, or norms in another realm.

Specifically, an effective strategy must bring about large-scale, long-term, structural change on all levels and transform all aspects of people’s lives:

- Individual values, beliefs, and temperament

- Personal interaction

- Small and large group dynamics

- Society-wide

Changes must come in all realms that determine how people work and interact as consumers, producers, providers, parents, teachers, students, clergypeople, laypeople, politicians, soldiers, and citizens:

- Political system: laws, voting; local, state, and national government; executive, legislative, and judicial branches

- Economic system: production, consumption, storage, transportation, property relations, trade, markets, money, investments, taxes, rents, profits, businesses, cooperatives, corporations

- Social connections: families, kinfolk, cliques, communities, racial and ethnic groupings, clubs, workplaces, cities, nations

- Institutions: schools, businesses, churches, associations, military forces, and government agencies

- Culture: language, values, beliefs, education, religion, ceremonies, work, play, stories, humor, literature, music, theater, television, movies, the Internet

Reliant on Ordinary People

On Politics: When our people get to the point where they can do us some good, they stop being our people.

Progressive activists must rely primarily on themselves and ordinary people in their communities, not on members of the elite, the news media, politicians, or liberal foundations. Though these entities are potent and sometimes provide useful help, more often they steer change toward token reform rather than fundamental transformation.

Democratic and Responsive

To achieve the goal of deep democracy, a viable strategy for change must be democratic in its processes and it must foster a broad democratic structure that is responsive to all people. A good strategy must also be responsive to criticism and include a positive way for people to question change methods. Throughout the change process, activists must continually evaluate their own efforts and be open to outside criticism.

I know of no safe depository of the ultimate powers of society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion by education. This is the true corrective of abuses of constitutional power.

Focused on Ending Oppression, Not Toppling Individual Oppressors

A strategy for thorough change must eliminate the real, structural sources of oppression — not just attempt to topple current authorities and replace them with progressive activists. Activists are inherently no more moral than the present rulers are. Every person is capable of oppressing others, no one is so virtuous that she is immune to temptation, and no one is so perfect that she will never err.

Only the truth is revolutionary.

Everyone is vulnerable to the corrosive effects of power. In fact, given the way leaders are idolized and indulged in our society, taking the reins of power often corrupts even those who are most caring and conscientious. Moreover, because of the way humans react to emotional injuries, those who have suffered the greatest oppression are often those most likely to “act out” the same kind of oppression if they are given the chance.

The particular role we play in our life — saint, sinner, member of the power elite, ordinary person, progressive activist — mostly depends on circumstances beyond our control. None of us chose our parents or our life experiences, they just happened to us. It is ridiculous to fault someone for having cruel parents, growing up deprived of necessities, or being immersed in racism. It is equally silly to commend someone else for having loving parents, having all her needs met, and being immersed in tolerance.

With this understanding, the struggle to create a good society can be seen in a new way. It is not a competition between good and bad people. Rather it is competition between degrading and damaging tendencies on the one hand and nurturing and cooperative tendencies on the other (see Figure 4.1).

[Picture of Figure 4.1]People often conceive of the struggle to create a good society as a giant battle with evil people on one side and saints on the other. Alternatively, they imagine powerful government or business leaders on one side and regular people on the other. However, it is not that simple.

Even the most tyrannical or corrupt authorities are human beings who love their families and friends. Just like everyone else, they want to live gratifying lives of joy and worth. They are not the stereotypical evil enemies depicted in melodramas. On the other side, the downtrodden are not all virtuous heroes. A thoroughly trampled and relatively powerless person can still abuse others: an elderly, homeless alcoholic may scream at a passerby, molest a child, or ignite a destructive fire. Moreover, regular people who oust a tyrant and assume the mantle of power can easily become as tyrannical as the previous authorities.

Creating a good society requires ending all oppression, not just changing the identity of the oppressor and oppressed. It also means creating positive and supportive institutions, not just tearing down oppressive structures.

As the figure above shows, it is more useful to view the effort to create a good society as a struggle to influence society and its people, institutions, and cultural norms. The positive forces of knowledge, cooperation, compassion, constructive socialization, and goodwill push in the direction of a good society as the negative forces of ignorance, domination by elite interests, and destructive cultural and emotional conditioning push the other way.

Nonviolent

Violent strategies typically produce a great deal of destruction and heartbreak, and do not end domination — they usually only shift oppression from one place to another. Violent strategies also do not usually overcome destructive cultural norms or alleviate dysfunctional emotional conditioning.

There are only two forces in the world, the sword and the spirit. In the long run the sword will always be conquered by the spirit.

A strategy for fundamental progressive change must therefore use nonviolent means that nurture people and bring out their best behavior. Effective change efforts must not demean or dehumanize people. Instead, change efforts must either persuade people or sensitively coerce them to stop their harmful behavior. Change efforts are most potent when they penetrate deeply into opponents’ hearts, dissolving rigid, patterned behavior and kindling compassion and goodwill.

Moral, Principled, True to Ideals, with the Means in Harmony with the Ends

More generally, a good strategy for change must rely only on means that are harmonious with the good society we seek to create. Many strategies for change are clearly unsuited to creating or maintaining a good society and cannot be used. Even seemingly innocuous change efforts can veer off in a counterproductive direction if they are not strictly aligned with morality and principle.

Always do right. This will gratify some people, and astonish the rest.

Laudatory goals and courageous, selfless action are valuable in inspiring people — motivating them to accomplish more than they could imagine under ordinary circumstances. Reaching toward high ideals encourages people toward selfless generosity.

Figure 4.2 contrasts several important progressive behaviors and attitudes with non-progressive ones.

[Picture of Figure 4.2]Figure 4.2: Progressive Behavior and Attitudes

| Progressive* | Not Progressive |

|---|---|

| Belief in the possibility of a better society | Belief that not much can or should be changed |

| Honest | Deceitful, manipulative |

| Moral, principled, conscience-driven | Immoral, unscrupulous, expedience-driven |

| Democratic (political, economic, and social) | Dominating, oppressive |

| Respectful, caring, loving, compassionate | Self-righteous, vindictive, punitive, hateful |

| Giving, generous | Demanding, greedy, stingy |

| Seeking the common good | Seeking self-interest |

| Cooperative | Competitive |

| Oriented toward mutual problem solving | Oriented toward defeating others |

| Flexible, open, responsive | Rigid, closed-minded, suspicious, intransigent |

| Nonviolent | Threatening |

| Sensible, reasonable, wise | Irrational, prejudiced |

| Passionate | Shutdown, alienated |

| Responsible, committed | Irresponsible, capricious |

* Throughout this book, when I refer to progressive activists, I mean they adhere or aspire to all of these characteristics.

Direct and Personal

A face-to-face interaction is more human and more effective in touching someone than an impersonal mass appeal. People are influenced much more by members of their immediate family, their friends, or their neighbors — those they have long experience with and have developed trust in — than by strangers or distant institutions. In addition, smiles, hugs, and physical warmth can convey love, support, and comfort much better than any words. Furthermore, while some people are motivated to work for change solely by noble passion or individual self-interest, more are attracted to the fellowship and solidarity they feel working in concert with their friends.

A Strategy for Democratic Transformation

Because it is so often misunderstood or downplayed, let me emphasize one important point: creating a good society is quite different from grabbing control of society’s power structure or manipulating the masses. To create a good society, progressive activists must transform deeply held cultural norms, overcome emotional blocks, redistribute power from the elite to everyone in roughly equal measure, and ensure people use their newly-acquired power responsibly and compassionately for the common good. To create a truly good society, activists must make these sweeping changes without establishing another coercive power structure.

As the twig is bent, so grows the tree.

I can see only one way to bring about this transformation democratically: activists must prepare people to take power and prepare them to assume power responsibly once they have taken it. In order not to be dictatorial, activists can challenge people, offer information, and provide support, but they cannot force people to act in any particular way. Therefore, the main activities of progressive activists must be to develop and consistently convey alternative ideas to large numbers of people and help them integrate these ideas into society as they see fit.

If people find these ideas valuable, they will eventually adopt them, just as progressive activists have adopted them for themselves. If people do not like these ideas, then as free citizens, they must be able to reject them.

One cannot impose a cooperative, democratic society on people — they must adopt it and claim it as their own. Activists who are truly progressive cannot use force or trickery; we can only serve as mentors and midwives, showing the way and facilitating the birth of a new society. Our means must reflect our desired ends if we want our means to lead to those ends.

Mass Education and

Powerful Social Change Movements

As this discussion indicates, an effective strategy for progressive transformation depends on educating and transforming virtually everyone in this country so they can then democratically choose a good society. Since the mass media are not suitable for broadcasting ideas about fundamental progressive change, and progressive activists have little control over the media anyway, activists must instead use more direct means.

A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or, perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: and a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.

As I envision it, advocates for progressive change would personally reach out to people — one by one when necessary — until they have touched essentially every person in this country. Activists would spend much of their efforts interacting directly with people — listening, talking, and discussing ideas, promoting the desirability of progressive change, showing how progressive ideas could work, and counseling and supporting people as they changed.

However, this would not be a completely individual activity. Progressive activists would join together in grassroots change organizations that would provide them with mutual support, greater visibility, and collective power. Some of these organizations would directly challenge institutions while others would build alternative institutions that would eventually displace conventional institutions. In this way, each grassroots organization could directly reach hundreds of people and indirectly affect thousands with little interference from the power elite. With enough organizations spanning the country, they could influence everyone.

Changing People’s Perspectives

Some people are persuaded by reading an article or book, others by watching a television show. However, most people change their perspectives on important issues only after a series of convincing experiences:

- They witness horrible events and see that current institutions or authorities are unresponsive.

- They learn about better alternatives.

- They see that others are working to implement these alternatives.

- They watch authorities ignore problems, repress dissent, crush positive alternatives, and lie. They discover the truth and realize they have been fooled.

- They ponder the situation for a time and talk the issue through with a trusted friend. New ideas settle into their consciousness.

- They see how they might work with others to implement alternatives.

- They believe their efforts working for change are likely to succeed.

- They see people they know who are happy in similar post-change institutions.

Each change organization would not only communicate with people in its community, but it would also offer a safe, supportive environment for educating its own members. Surrounded by a progressive subculture, members would have a chance to learn new ideas and behaviors, plumb the depths of these ideas over an extended period, try them out in interactions with others, and thoughtfully consider how to integrate them into their own lives — all with little fear of retribution.

If hundreds of these grassroots organizations were networked or allied together by an issue or constituency, they would comprise a social movement potentially capable of influencing millions of people, undercutting the existing order, and bringing about large-scale change. If a large number of these progressive movements were working for change collaboratively (in coalition, federation, or alliance), they could fundamentally transform society using completely democratic and minimally coercive means.

Six Essential Components of an

Effective Strategy

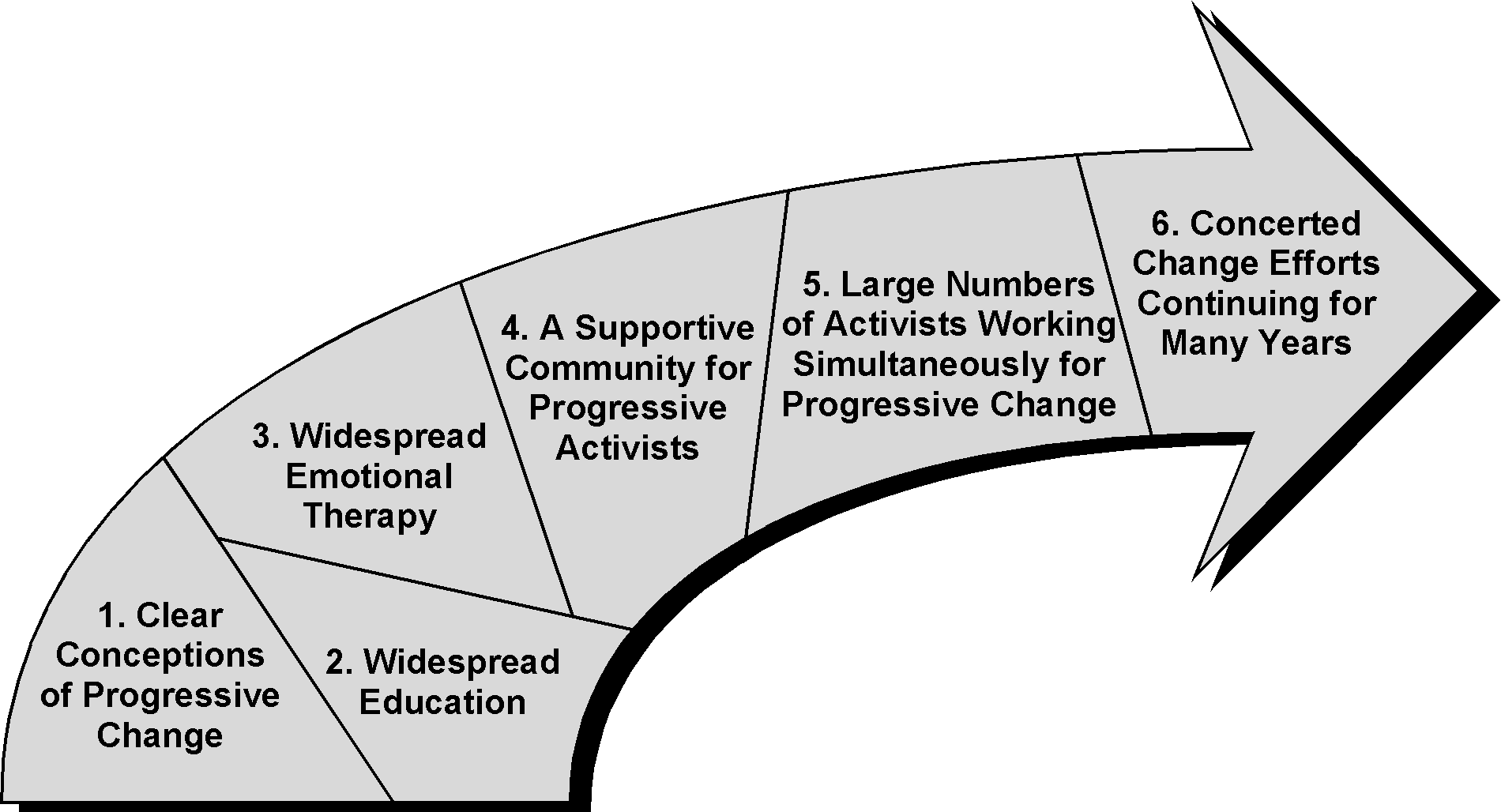

As briefly outlined here, this mass education strategy seems quite simple. However, it encompasses more than is first apparent. To be effective, this strategy includes these six essential components:

[Picture of Figure 4.3]Figure 4.3: Essential Components of an Effective Strategy

1. Clear Conceptions of Progressive Change

Without knowing what a good society might be like or knowing feasible methods to create one, most people will never consider working for change. Moreover, without a clear understanding, they probably will not even passively endorse the work of progressive activists. Therefore, it is essential that a great many people believe it is possible to transform society and understand how to do it. Initially, only progressive activists must understand, but eventually almost everyone must have a clear sense.

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to walk from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat

“I don’t much care where,” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you walk.”

Progressive activists must develop and convey both an inspiring vision of a truly good society and a comprehensive and workable plan for realizing that vision.[8]

A Clear Vision of a Good Society

Chapter 2 listed the basic elements that I believe should be part of a good society and detailed a few particular aspects of such a society. I hope this skeletal framework can serve as the basis for a more comprehensive vision. As we move towards a good society, this vision must be expanded to address all parts of society and refined in light of new experience and the desires of every person.

A Comprehensive and Feasible Strategy for Change

A comprehensive and feasible plan for social transformation would galvanize many people to action. Such a plan would attract and excite those who are now discouraged by the apparent ineffectiveness of current progressive change efforts. It would alleviate newcomers’ fear that progressives might lead them over a cliff or down a slow, winding path to nowhere. Moreover, a comprehensive plan would provide a reassuring context for the work of current progressive activists when their efforts seem inconsequential or unimportant. A clear plan could also help keep activists on track and bolster their fervor at those crucial times when frustrating setbacks might otherwise lead them to try unsavory shortcuts or give up.

For a progressive change plan to be comprehensive and feasible, it must be:

- Realistic — Since fundamental change of society is an enormous goal, an effective change strategy must be grounded in a realistic assessment of all the political, economic, social, and cultural forces in society. Like a strategy for war, it must consider the forces favoring and opposing progressive change and the power and resources (people, weapons, money, and influence) each side has at its command. A realistic plan must show how to overcome the obstacles described in the last chapter and incorporate the lessons from history listed above.

- Thorough — Just as a general contractor might plan construction of a building, each step must be laid out in a clear way — who does what first, how that step leads to the next step, what we can expect to follow, and so forth. Not every particular has to be specified completely, but the plan must be detailed enough that skeptics (potential supporters) find it realistic after careful scrutiny.

- Encompassing — The plan must seek to transform all aspects of society fundamentally, from humanizing the ways that people interact with each other to democratizing the large institutions of society. It cannot merely shift power from one group of elite power brokers to another. Rather, it must empower citizens to take charge of societal institutions and to operate them equitably and compassionately for the common good.

- The plan must also consist of many, diverse campaigns for change that affect a wide range of people and effectively address a variety of important issues so that, in total, they comprise a comprehensive change strategy.

- Practical — The plan must be practical. It must rely on techniques and tactics of demonstrated effectiveness. Furthermore, these methods must be within the realm of experience and the bounds of morality of the people who will use them.

- Honorable, Lofty, Inspiring — To garner widespread support, the plan must rely on actions that most people in society consider morally sterling. Furthermore, to have a chance of working, the plan should inspire people to their best behavior — bringing out the compassion, empathy, and concern for the common good that usually emerge only in times of disaster or war.

- Consistent with Goals — If it is to bring about truly fundamental change, the plan must employ the tools of a good society as it creates that society. The plan itself must be inclusive of all people, cooperative, just, and democratic. All aspects of the plan must build towards a good society.

- Flexible and Adaptable — Mistakes and changing circumstances require that evaluation, correction, and change be built into the plan. Otherwise, change efforts will more than likely become rigid, inappropriate, and possibly even tyrannical.

Since creating a good society is a long process — stretching over decades — the change process will likely evolve through several distinctive stages: building a foundation in the early years, making critical changes in the middle years, and consolidating the changes in the later years. It will encompass a variety of large campaigns, each with many smaller sub-campaigns.

This book is my attempt to formulate a preliminary plan for change that meets these criteria. The plan outlined here must, of course, be expanded and refined over time to accommodate changes and new understandings.

2. Widespread Education

Somehow progressive activists must convey a vision of a good society to the vast majority of people and help them develop the skills necessary to create and maintain a good society. This requires an educational process capable of reaching virtually everyone.

In addition, progressive activists must acquire the knowledge and skills they need to bring about change. This requires another educational process geared specifically to current and future activists.

Since a democratic society repudiates the principle of external authority, it must find a substitute in voluntary disposition and interest; these can be created only by education.

Learn How Society Actually Functions

People must learn how to recognize the myths that obscure understanding of our society. They must begin to see how destructive and cruel our society really is. They must learn the truth about how it actually functions and who really has power: who makes decisions and how they implement them. People must also learn that it is possible for ordinary people to gain power and struggle for positive change.

Learn to Practice Democracy and Cooperation

To create and maintain a good society, the vast majority of people must also have a vision of a good society and be able to practice democracy, cooperation, and other progressive means for working and living together. Many people have never seen these methods practiced at all, and most have never seen them practiced well. Of those few people who have any experience with these methods, most have not learned how to use them well.

Enlighten the people generally, and tyranny and oppressions of body and mind will vanish like the evil spirits at the dawn of day.

Instead, people practice what they know: They boss their children and spank them when they do not obey. They tolerate schoolyard bullying. They support rabid sports competition. They endorse schools that rely on rote memorization and mindless regurgitation. They accept undemocratic voting procedures. They acquiesce to domination by people up the hierarchy. They pass along to their children their misconceptions, prejudices, fears, and addictions.

Skills required for a good society include the ability to:

- Read, write, and do arithmetic at a basic level

- Think critically and sort out conflicting claims

- Listen well and empathize with others’ positions

- Convey ideas to others by speaking clearly

- Cooperate with others and work in a team

- Solve problems creatively

- Make decisions cooperatively and democratically

- Share equitably with others

- Resolve conflict well

- Stand up to prejudice

- Nonviolently challenge injustice and imbalances of power

- Rear children in a way that preserves the child’s self-esteem and inculcates responsibility

Schools in the United States address some of these areas and impart a rudimentary level of skill, but far more is needed.

For example, our society is ostensibly democratic, but the democracy most people first see is the charade practiced by their school Student Council. Student Councils are usually impotent bodies populated by ambitious students who run for office mainly out of the desire to build up their résumés or to impress their parents. Student Council members are typically elected by a small minority of students who voted primarily because of their candidate’s popularity or flamboyant campaign tactics. Council members are generally ignorant about policy issues, and the Council usually has no real power to change any important policies anyway.

Seeing this, students learn that democracy is a silly game played primarily by attention-seekers. Their cynicism towards democracy then extends to local, state, and national government, especially when they learn that corruption and fraud are commonplace.

Which is the best government? That which teaches us to govern ourselves.

Real democracy is, of course, quite different from this. It requires knowledgeable and assertive citizens who can debate real issues and come up with decisions that best address the common good. People must know how to research issues, how to formulate positions, and how to explain their perspective to others. They must know how to hear others’ perspectives, how to ask penetrating questions, how to develop solutions, and how to work together to integrate various perspectives into a good decision that truly addresses community needs and to which everyone can consent. They must also know how to implement these decisions in a fair and timely manner.

Since people have not grown up in a good society and learned these skills by watching others, everyone must be shown or taught them more directly. Since the public schools do not teach these skills, progressive activists must. So an effective change strategy must include an educational process that can convey these ideas and skills thoroughly enough that most people can acquire them.

Learn to Overcome Destructive Cultural Conditioning

As described in the last chapter, every society has strong cultural norms, most of them benign. However, some norms are destructive and must be changed before a good society can flourish.

Habit is habit, and not to be flung out of the window by any man, but coaxed downstairs a step at a time.

Societal norms change slowly, but individuals often adopt new cultures quite readily. Robert F. Allen and the staff of the Human Resources Institute discovered, to their dismay, just how quickly young people could adopt delinquency culture.[9] In their research in the early 1950s, they followed black families that had recently moved from the South or Puerto Rico to urban areas in the Northeast. Many black youngsters who had never been involved in delinquency were transformed into full-fledged miscreants in just six to eight months. Clearly, urban ghettos provided an effective training program. Moreover, the process took place in such a way that the young boys only barely noticed what was happening to them.

In a similar fashion, a person will adopt a more positive culture if immersed in a favorable environment. Allen and his colleagues found that to develop positive behavior such an environment should include these seven elements:

- Direct communication of what behavior is acceptable and expected and why.

- Modeling of this positive behavior by others, especially those with the most influence.

- Commitment of time and resources to good behavior.

- Training and practice of positive behavior so a person can actually do it when she tries.

- Rewards for positive behavior (attention, praise, awards, money) and penalties for destructive behavior (confrontation, condemnation).

- Constant contact with people who act well and limited contact with people who act badly. When it is impossible to change the larger culture, this contact can be provided by a positive mini-culture in which everyone acts well within the local environment.

- Immediate contact with people who act well when a person first comes into the environment since a person is especially receptive to new norms when she first tries to establish friendships and fit in.

The great law of culture is to let each become all that he was created capable of being; expand, if possible to his full growth; resisting all impediments, casting off all foreign, especially noxious adhesions, and show himself in his own shape and stature, be those what they may.

Generally, people take several steps to overcome their destructive cultural conditioning:

- Open Up — They expose themselves to other cultures and new ideas. Many people learn through travel or by meeting travelers from other places. Some people attend lectures, workshops, theater, or concerts to expose themselves to new ideas. Others survey local churches or social clubs, looking for unique perspectives. Books, magazines, movies, radio, and television can also provide a window into other worlds.

- Observe — They become aware that cultural norms shape their beliefs, values, and feelings. They notice the ways these norms are taught and the ways they are enforced. They recognize that other people have different ideas and different ways to do things.

- Evaluate — They compare their own beliefs, values, and feelings to those of other people to see which are more humane and useful.

- Decide — They decide to adopt more humane beliefs and feelings and decide to act in new, more appropriate or useful ways.

- Act — They behave more like their ideal. They restrain their hurtful behavior and change their relationships with others.

- Practice — They practice their new behaviors and beliefs repeatedly until these behaviors and beliefs feel “normal.”

- Create a Subculture — They find other people who also want to adopt new cultural norms and interact with them in the new ways, thus creating their own subculture with its own positive norms.

To deliberately adopt and adhere to new cultural norms, a group should ensure that all aspects of the group are oriented toward the new norms. Each individual must be supported and encouraged to adopt the new culture, and the group as a whole must explicitly choose the new cultural norms and try to move towards them. Moreover, the leaders of the group must adopt the new norms and allocate resources to move the group towards them. The policies, procedures, and programs of the group must also be brought into alignment with the new norms.

Changing our whole society’s cultural norms will require changing the culture of the society’s leadership as well as societal policies and institutions.

Learn to Change Society

As detailed in the previous chapter, progressive activists now usually learn how to create change by watching other activists. Since these other activists are seldom very knowledgeable about theory, strategy, and tactics or skilled in effective change techniques, new activists are often taught poorly. They generally learn slowly through trial and error. Consequently, many new activists burn out long before they have a chance to learn much.

To be effective, activists must learn to design powerful and exciting campaigns that move toward fundamental change, and they must learn how to develop and promote positive cultural norms. They must learn how to avoid and overcome dysfunctional patterned behavior, infighting, groupthink, and hopelessness. They must also learn how to support other activists and how to arrange emotional support for themselves.

Moreover, activists must learn — even better than everyone else — how to practice democracy and cooperation. Obviously, activists cannot show the way to others unless they have already traveled the path and know it well. An effective change strategy must therefore include an educational process that can expeditiously pass on to most activists all the knowledge and skills they need.

3. Widespread Emotional Therapy

One will rarely err if extreme actions be ascribed to vanity, ordinary actions to habit, and mean actions to fear.

A good society cannot exist if everyone suffers from emotional trauma and regularly acts out in inappropriate ways. Moreover, progressive activists cannot work effectively to create a good society if they continually carry around their own emotional baggage.

To reduce emotional trauma, an effective strategy for change must offer effective emotional therapy to most people. It must include ways for people to learn how to stop inflicting their dysfunctional behavior on others and help them learn means to interrupt other’s inappropriate behavior. They must also learn how to overcome their addictions and inhibitions. Moreover, an effective strategy must provide a way for progressive activists to work through their emotional conditioning and heal enough so they can think clearly in stressful situations, confront other peoples’ worst behavior, and quickly rebound from attacks.

Steps to Emotional Health

Generally, people take several steps on the way to emotional health:

- Observe — They notice the ways their behavior is inappropriate or unproductive, especially the ways it is hurtful to themselves or others. They observe the ways other people act that are more appropriate, effective, or compassionate.

- Digest — They ponder and analyze their emotional responses. They think, talk, and write about their life and the traumas that they have suffered in childhood (and more recently). They consider how past traumas affect their current behavior. They notice the decisions they have made over the years and how those decisions have led to the life they now have.

- Explore Possibilities — They envision new ways to feel and behave that are more appropriate and self-affirming. They consider other ways to live, other decisions they might make, and new directions they might go.

- Decide — They decide to act in new, more appropriate or useful ways, and they work to change their conception of themselves to reflect their true self-worth.

- Plan and Arrange — They arrange for other people to help them act in these new ways. They plan ways to escape or change their violent or degrading home life or workplace. They consider who can provide support and encouragement as they move forward.

- Act — They behave more like their ideal. They avoid or escape from hurtful situations, restrain their hurtful behavior, change their relationships with others, and begin to feel good about themselves. They focus on pleasant activities and their successes. They seek out supportive friends.

- Emote — As feelings of anger, frustration, fear, and confusion arise, they express these feelings in a safe and supportive environment — either with a counselor or with family or friends.

- Move On — They avoid hurtful situations, and they focus on the future. They move on to a better life and continue working through any other emotional barriers they discover in themselves.

Autobiography in Five Short Chapters

Chapter One: I walk down the street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I fall in. I am lost… I am helpless. It isn’t my fault. It takes forever to find a way out.

Chapter Two: I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I pretend I don’t see it. I fall in again. I can’t believe I’m in the same place. But it isn’t my fault. It still takes a long time to get out.

Chapter Three: I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I see it is there. I still fall in… It’s a habit… but, my eyes are open. I know where I am. It is my fault. I get out immediately.

Chapter Four: I walk down the same street. There is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I walk around it.

Chapter Five: I walk down another street.

Some people can work through their emotional wounds and choose positive new directions without any help. They typically use several techniques. Some think over their life while walking in the woods or sitting on a mountaintop. This allows them to sort out the truth without intrusive interference by others, and it costs nothing. Others write their thoughts in a journal. Some people give themselves daily affirmations and encouragement to move forward.[11] Some people immerse themselves in science fiction, fantasy stories, role-playing, spiritual explorations, or even hallucinogenic drug experiences to kick themselves out of their rigid patterns and to push themselves towards alternative perspectives and activities. Though these methods are effective for many people, there is always a danger that they will cause some people to veer off into a fantasyland instead of staying grounded in the reality of their lives.

A hearty laugh gives one a dry cleaning, while a good cry is a wet wash.

To surmount severe emotional trauma, most people need assistance. Skilled therapists or members of the clergy can help people by:

- providing a safe, compassionate environment

- providing nurturance and encouragement

- providing an objective, uninvolved point of view

- providing solid information about emotional traumas, their sources, and how to overcome them

- suggesting alternative behaviors and activities

- serving as a role model of emotional health and appropriate behavior

Since good therapists are expensive and members of the clergy have limited time, many people rely instead on mutual support and cooperative counseling with their friends or colleagues. To work well, peer counselors must devote at least as much energy as, and develop skills comparable to, beginning therapists.

By starving emotions we become humorless, rigid and stereotyped; by repressing them we become literal, reformatory and holier-than-thou; encouraged, they perfume life; discouraged, they poison it.

Through emotional therapy, activists can overcome many negative feelings and behaviors and thus act intelligently, flexibly, and passionately. Good emotional therapy can dramatically improve an activist’s ability to perform social change work. It can also make her much happier.

My own counseling experience is quite positive. For ten years, I was involved with a peer counseling organization. Each week I attended a two-hour class taught by a more experienced counselor. Every week I also had two or three counseling sessions, each with a different class member. In these sessions, I would counsel my partner for an hour, then we would switch, and she would counsel me for an hour. Since leaving this organization, I still have a weekly counseling session and attend a support group every three weeks. With this support, I have overcome many of my limitations. Stormy emotions no longer run my life, and I am now able to redirect this energy into positive change activity.

Do the best you can — you can’t do any better than that.

Still, even with good counseling and solid support, emotional injuries are difficult to heal. It often takes years to sort through the emotions and more years for their intensity to subside. The only long-term solution is prevention — raising children in a loving and supportive environment. When efforts to create a good society begin to succeed (especially in eliminating childhood traumas like child abuse, neglect, and poverty), there will be more emotionally healthy people around. In the meantime, we must accept that many people will have emotional wounds.

The Healing Power of Positive Change Work

Powerful, positive social change work can be very effective in helping people overcome their dysfunctional emotional conditioning. The camaraderie that comes from working with others and the ennoblement that comes from working for a righteous cause can counter feelings of loneliness, low self-esteem, alienation, purposelessness, and hopelessness.

4. A Supportive Community for Progressive Activists

Activists thrive best when immersed in a supportive community that practices positive cultural norms. Such a group can push each activist to act her best. In such an environment, activists can also try out innovative ideas without fear of condemnation.

People are more fun than anybody.

When times are rough, progressive activists must get both practical and emotional support from others. A supportive community can furnish this assistance, offer nurturance, and provide a safe space to heal from attacks. When activists know they have access to such a safe, supportive community, they are less afraid of being attacked by powerful interests or being abandoned by unsupportive family or disgruntled friends. This results in happier, clearer-thinking activists who are more compassionate and can take bolder and wiser action.

A strong, supportive community of activists, in which everyone is usually in good emotional health, is also more resistant to infighting. Whenever an activist exhibits signs of stress or trauma, others can move in with loving support. They can interrupt that person’s destructive behavior and guide her back to emotional health before she hurts anyone else. In this way, no one ever goes overboard, and the community can remain harmonious.

In addition, a supportive community can provide:

- Shared resources (such as computers, automobiles, tools, and so on)

- Financial aid (including loans and grants)

- Help with basic life maintenance (help with housework, food preparation, transportation, childcare, eldercare)

- Help in learning skills or acquiring knowledge

- Companionship for shared leisure activities (including singing, massage, and play)

- Supportive interaction (active listening, encouragement, provocative questioning, cuddling, support for nonconforming behaviors and dissenting ideas)

- Help in dealing with conflicts

- Long-term social interaction (providing stability and commitment)

- Help with progressive change efforts

- Help in fending off outside attacks or threats

- Connection to more distant activists who can help in difficult times

Traditionally, support for activists has been provided by lovers, secretaries, subordinates, or hired consultants (such as mediators and bookkeepers), but these resources are generally not available to progressive activists who are dedicated to equality or too poor to hire assistants. A supportive community in which activists voluntarily and mutually support one another offers a better way.

Living Simply

By living simply, activists can reduce their dependence on society, escape many pressures to conform to the dominant culture, and free up more time and resources for progressive change. Simple living is also more ecologically responsible.

Activists can live more simply by:

- Sharing housing, vehicles, tools, books, equipment, facilities, and so on

- Ignoring fashion trends and beauty regimens

- Limiting purchases to essentials — hand-making gifts, toys, and the like instead of buying them

- Fixing and mending items instead of buying new ones

- Substituting simple pleasures like hiking, conversation, storytelling, shared play, music, and reading for expensive luxury goods and tourist travel

- Reducing health care needs by exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, receiving massages, and engaging in meditation, counseling, and sufficient leisure

5. Large Numbers of Activists Working Simultaneously for Progressive Change

As explained above, both morality and practicality dictate that a good strategy must use democratic and non-coercive means to bring about fundamental change. This means the vast majority of people in this country must at least passively tolerate each of the major changes.

Light is the task where many share the toil.

To reach and influence the vast majority of people requires that large numbers of progressives become advocates for fundamental change. Only when there are large numbers of activists can they personally inform, persuade, encourage, inspire, and support each person to learn and change at her own pace.

Moreover, only large numbers of activists can simultaneously challenge scores of harmful existing institutions, build alternative institutions to replace them, and resist the immense might of the power elite. With large numbers, activists could challenge elite interests from so many directions at once that they would be overwhelmed and their capacity to retaliate would diminish. This, in turn, would offer hope that real change was possible, which would inspire even more people to join the effort and would energize activists to work harder.

Currently in the United States, millions of progressive-minded people desire positive change. However, only a relatively small percentage of these people actively work for comprehensive, fundamental change.

Based on my experience and research, I estimate about 50,000 people work a sizable number of hours each week for fundamental progressive change. Probably an additional 300,000 progressive advocates talk with their family and friends about fundamental change and occasionally work for it. Perhaps several hundred thousand more people desire fundamental change, but do little beyond contributing small amounts of money to progressive organizations.*

* These estimates take into account all the employees and volunteers of change and service organizations, political officeholders and their staffmembers, government employees, public-interest lawyers, labor organizers, teachers, students, and ministers. Figure C.4 in Appendix C provides more details about these estimates.

Based on my experience, I estimate that fundamental change will require at least three times as many progressive activists and advocates — at least a million people working actively for fundamental, comprehensive change. To transform society, these activists and advocates must also be more experienced, skilled, and capable than their counterparts are today.

6. Concerted Change Efforts Continuing for Many Years

By the fall of drops of water, by degrees, a pot is filled.

To provide sufficient time to reach the vast majority of people in this country and enough time to sway most of them profoundly, these progressive activists must maintain a high level of change activity over many years. Moreover, enough decades must go by so that those people who are unable to change can grow old, pass away, and be replaced by young people more receptive to progressive ideals. It also takes decades to design and build alternative structures. Therefore, I estimate it would take at least forty years of concerted effort to bring about a comprehensive transformation of society.

An Effective Strategy that

Incorporates these Components

Energy and persistence conquer all things.

If carried out well, I believe the change strategy outlined here, encompassing these six essential components, would be sufficient to overcome the five main obstacles to fundamental progressive change described in the previous chapter. This strategy — based on mass education and powerful social change movements — would also enable progressive activists to bring about fundamental transformation of our society in a principled way consistent with participatory democracy and other progressive ideals.

The next six chapters expand on this general strategy and detail a specific program for implementing it.

Next Chapter:

5. A Strategic Program to Create a Good Society

Notes for Chapter 4

A few scholars have argued that some prehistorical societies were gentle, compassionate, equitable, and pacifistic, that is, good societies. See, for example, Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future (San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1987, HQ1075 .E57 1987). Even if this is true, they assume that these societies evolved naturally from small hunter-gatherer societies, so no one had to transform a bad society into a good one, as we must do.

For an excellent summary of many historical change movements and theories, see David Miller, ed., The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Thought (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, 1987, JA61 .B57 1987). For a good summary of the history of leftist movements in the United States in the twentieth century, see John Patrick Diggins, The Rise and Fall of the American Left (New York: W. W. Norton, 1992, HN90 .R3D556 1992).

Jack Goldstone, “Revolutions, Theory of,” The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Thought, pp. 436–441.

See, for example, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Communist Manifesto (1848), and Karl Marx, Capital (1867), in Lewis S. Feuer, ed., Marx and Engels: Basic Writings on Politics and Philosophy (Garden City, NY: Anchor, Doubleday, 1959, HX276 .M27736).

Marxist Ronald Aronson persuasively argues that capitalism has changed in ways not anticipated by Marx. After careful study, he concludes that

Marxism as a revolutionary project, compelling as it has been, belongs to an earlier age. Any new radical project, for all its continuing commitment to emancipation and social justice, will look and feel very different.

Ronald Aronson, After Marxism (New York: Guilford Press, 1995, HX44.5 .A78 1994), p. 39.

See Lawrence Goodwyn, The Populist Moment: A Short History of the Agrarian Revolt in America (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1978, E669 .G672 1978).

Michael Fullerton, ed., What Happened to the Berkeley Co-op? A Collection of Opinions (Davis, CA: Center for Cooperatives, University of California, 1992).

Note that some co-ops are still doing well, and the co-op movement is still strong in some places.

Marxist Ronald Aronson argues this point clearly:

No new radical project is possible that is not constructed around a unifying and compelling vision of a different social order. Any new movement, to be effective, will have to provide a convincing account of the major problems caused by the existing order, principal structures to be changed, and groups of people likely to struggle for such changes. It will have to nourish powerful convictions about the kinds of changes being pursued and about its participants’ ability to achieve them. It will have to mobilize people — by generating wide solidarity, giving people a sense of political and personal direction, and by simultaneously promoting self-confidence and realism. Its members will have to be sustained by a clear understanding of being wronged, deep convictions about being right, an awareness of being strong, a sense of building a new future, an effective understanding of the present, and a sense of hope and possibility.

Ronald Aronson, After Marxism (New York: Guilford Press, 1995, HX44.5 .A78 1994), p. 231.

On page 244, Aronson describes some essential features of a powerful movement. The people in it must:

• Have the will to achieve their goal of changing the social order

• Feel they have the right to that change

• Feel they are capable of achieving and enjoying that change

• Believe it is historically possible to achieve the change

Robert F. Allen, Beat the System!: A Way to Create More Human Environments (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1980, HM101 .A574), pp. vii, 56–57.

Portia Nelson, “Autobiography in Five Short Chapters,” There’s a Hole in my Sidewalk: The Romance of Self-Discovery (Hillsboro, OR: Beyond Words Publishing, 1993), 2–3. Used with the permission of Beyond Words Publishing. This book is available here.

I have found a guided meditation audiotape to be quite useful in helping me relax and visualize overcoming barriers and moving toward my highest ideals. Prepared by Dr. Emmett Miller and called “Healing Journey,” it is available for $12 from: Source Cassette Learning Systems, Inc., 131 East Placer St., P.O. Box 6028, Auburn, CA 95604, 800-528-2737, dmae@drmiller.com

http://www.drmiller.com/manage.html.

IcD-4-8.05W 5-5-01

The Vernal Project

The Vernal Project